5. 结构型模式 - 外观模式

亦称:?Facade

?意图

外观模式是一种结构型设计模式,?能为程序库、?框架或其他复杂类提供一个简单的接口

?问题

假设你必须在代码中使用某个复杂的库或框架中的众多对象。?正常情况下,?你需要负责所有对象的初始化工作、?管理其依赖关系并按正确的顺序执行方法等。

最终,?程序中类的业务逻辑将与第三方类的实现细节紧密耦合,?使得理解和维护代码的工作很难进行。

?解决方案

外观类为包含许多活动部件的复杂子系统提供一个简单的接口。?与直接调用子系统相比,?外观提供的功能可能比较有限,?但它却包含了客户端真正关心的功能。

如果你的程序需要与包含几十种功能的复杂库整合,?但只需使用其中非常少的功能,?那么使用外观模式会非常方便,

例如,?上传猫咪搞笑短视频到社交媒体网站的应用可能会用到专业的视频转换库,?但它只需使用一个包含?encode-(filename, format)方法?(以文件名与文件格式为参数进行编码的方法)?的类即可。?在创建这个类并将其连接到视频转换库后,?你就拥有了自己的第一个外观。

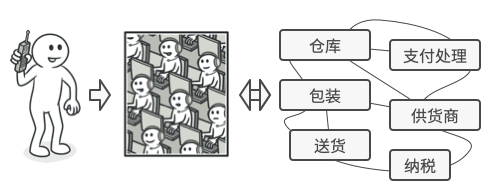

?真实世界类比

电话购物。

当你通过电话给商店下达订单时,?接线员就是该商店的所有服务和部门的外观。?接线员为你提供了一个同购物系统、?支付网关和各种送货服务进行互动的简单语音接口。

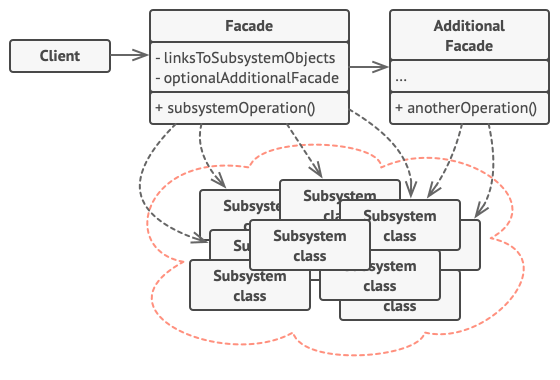

?外观模式结构

-

外观?(Facade)?提供了一种访问特定子系统功能的便捷方式,?其了解如何重定向客户端请求,?知晓如何操作一切活动部件。

-

创建附加外观?(Additional Facade)?类可以避免多种不相关的功能污染单一外观,?使其变成又一个复杂结构。?客户端和其他外观都可使用附加外观。

-

复杂子系统?(Complex Subsystem)?由数十个不同对象构成。?如果要用这些对象完成有意义的工作,?你必须深入了解子系统的实现细节,?比如按照正确顺序初始化对象和为其提供正确格式的数据。

子系统类不会意识到外观的存在,?它们在系统内运作并且相互之间可直接进行交互。

-

客户端?(Client)?使用外观代替对子系统对象的直接调用。

?伪代码

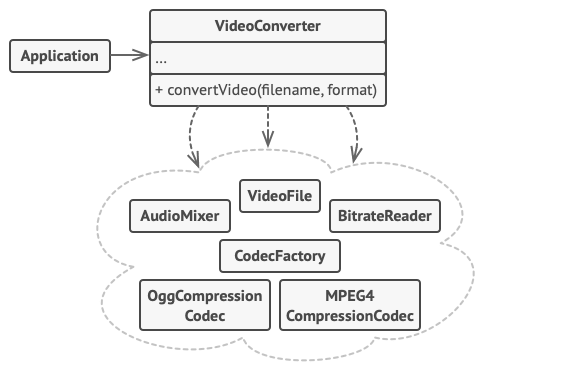

在本例中,?外观模式简化了客户端与复杂视频转换框架之间的交互。

使用单个外观类隔离多重依赖的示例

你可以创建一个封装所需功能并隐藏其他代码的外观类,?从而无需使全部代码直接与数十个框架类进行交互。?该结构还能将未来框架升级或更换所造成的影响最小化,?因为你只需修改程序中外观方法的实现即可。

// 这里有复杂第三方视频转换框架中的一些类。我们不知晓其中的代码,因此无法

// 对其进行简化。

class VideoFile

// ……

class OggCompressionCodec

// ……

class MPEG4CompressionCodec

// ……

class CodecFactory

// ……

class BitrateReader

// ……

class AudioMixer

// ……

// 为了将框架的复杂性隐藏在一个简单接口背后,我们创建了一个外观类。它是在

// 功能性和简洁性之间做出的权衡。

class VideoConverter is

method convert(filename, format):File is

file = new VideoFile(filename)

sourceCodec = (new CodecFactory).extract(file)

if (format == "mp4")

destinationCodec = new MPEG4CompressionCodec()

else

destinationCodec = new OggCompressionCodec()

buffer = BitrateReader.read(filename, sourceCodec)

result = BitrateReader.convert(buffer, destinationCodec)

result = (new AudioMixer()).fix(result)

return new File(result)

// 应用程序的类并不依赖于复杂框架中成千上万的类。同样,如果你决定更换框架,

// 那只需重写外观类即可。

class Application is

method main() is

convertor = new VideoConverter()

mp4 = convertor.convert("funny-cats-video.ogg", "mp4")

mp4.save()

?外观模式适合应用场景

?如果你需要一个指向复杂子系统的直接接口,?且该接口的功能有限,?则可以使用外观模式。

?子系统通常会随着时间的推进变得越来越复杂。?即便是应用了设计模式,?通常你也会创建更多的类。?尽管在多种情形中子系统可能是更灵活或易于复用的,?但其所需的配置和样板代码数量将会增长得更快。?为了解决这个问题,?外观将会提供指向子系统中最常用功能的快捷方式,?能够满足客户端的大部分需求。

?如果需要将子系统组织为多层结构,?可以使用外观。

?创建外观来定义子系统中各层次的入口。?你可以要求子系统仅使用外观来进行交互,?以减少子系统之间的耦合。

让我们回到视频转换框架的例子。?该框架可以拆分为两个层次:?音频相关和视频相关。?你可以为每个层次创建一个外观,?然后要求各层的类必须通过这些外观进行交互。?这种方式看上去与中介者模式非常相似。

?实现方式

-

考虑能否在现有子系统的基础上提供一个更简单的接口。?如果该接口能让客户端代码独立于众多子系统类,?那么你的方向就是正确的。

-

在一个新的外观类中声明并实现该接口。?外观应将客户端代码的调用重定向到子系统中的相应对象处。?如果客户端代码没有对子系统进行初始化,?也没有对其后续生命周期进行管理,?那么外观必须完成此类工作。

-

如果要充分发挥这一模式的优势,?你必须确保所有客户端代码仅通过外观来与子系统进行交互。?此后客户端代码将不会受到任何由子系统代码修改而造成的影响,?比如子系统升级后,?你只需修改外观中的代码即可。

-

如果外观变得过于臃肿,?你可以考虑将其部分行为抽取为一个新的专用外观类。

?外观模式优缺点

- ?你可以让自己的代码独立于复杂子系统。

- ?外观可能成为与程序中所有类都耦合的上帝对象。

?与其他模式的关系

-

? 外观模式为现有对象定义了一个新接口, 适配器模式则会试图运用已有的接口。 适配器通常只封装一个对象, 外观通常会作用于整个对象子系统上。 当只需对客户端代码隐藏子系统创建对象的方式时, 你可以使用抽象工厂模式来代替外观。 享元模式展示了如何生成大量的小型对象, 外观则展示了如何用一个对象来代表整个子系统。 外观和中介者模式的职责类似: 它们都尝试在大量紧密耦合的类中组织起合作。 外观为子系统中的所有对象定义了一个简单接口, 但是它不提供任何新功能。 子系统本身不会意识到外观的存在。 子系统中的对象可以直接进行交流。 中介者将系统中组件的沟通行为中心化。 各组件只知道中介者对象, 无法直接相互交流。 外观类通常可以转换为单例模式类, 因为在大部分情况下一个外观对象就足够了。 外观与代理模式的相似之处在于它们都缓存了一个复杂实体并自行对其进行初始化。 代理与其服务对象遵循同一接口, 使得自己和服务对象可以互换, 在这一点上它与外观不同。 ?

?代码示例

/**

* The Subsystem can accept requests either from the facade or client directly.

* In any case, to the Subsystem, the Facade is yet another client, and it's not

* a part of the Subsystem.

*/

class Subsystem1 {

public:

std::string Operation1() const {

return "Subsystem1: Ready!\n";

}

// ...

std::string OperationN() const {

return "Subsystem1: Go!\n";

}

};

/**

* Some facades can work with multiple subsystems at the same time.

*/

class Subsystem2 {

public:

std::string Operation1() const {

return "Subsystem2: Get ready!\n";

}

// ...

std::string OperationZ() const {

return "Subsystem2: Fire!\n";

}

};

/**

* The Facade class provides a simple interface to the complex logic of one or

* several subsystems. The Facade delegates the client requests to the

* appropriate objects within the subsystem. The Facade is also responsible for

* managing their lifecycle. All of this shields the client from the undesired

* complexity of the subsystem.

*/

class Facade {

protected:

Subsystem1 *subsystem1_;

Subsystem2 *subsystem2_;

/**

* Depending on your application's needs, you can provide the Facade with

* existing subsystem objects or force the Facade to create them on its own.

*/

public:

/**

* In this case we will delegate the memory ownership to Facade Class

*/

Facade(

Subsystem1 *subsystem1 = nullptr,

Subsystem2 *subsystem2 = nullptr) {

this->subsystem1_ = subsystem1 ?: new Subsystem1;

this->subsystem2_ = subsystem2 ?: new Subsystem2;

}

~Facade() {

delete subsystem1_;

delete subsystem2_;

}

/**

* The Facade's methods are convenient shortcuts to the sophisticated

* functionality of the subsystems. However, clients get only to a fraction of

* a subsystem's capabilities.

*/

std::string Operation() {

std::string result = "Facade initializes subsystems:\n";

result += this->subsystem1_->Operation1();

result += this->subsystem2_->Operation1();

result += "Facade orders subsystems to perform the action:\n";

result += this->subsystem1_->OperationN();

result += this->subsystem2_->OperationZ();

return result;

}

};

/**

* The client code works with complex subsystems through a simple interface

* provided by the Facade. When a facade manages the lifecycle of the subsystem,

* the client might not even know about the existence of the subsystem. This

* approach lets you keep the complexity under control.

*/

void ClientCode(Facade *facade) {

// ...

std::cout << facade->Operation();

// ...

}

/**

* The client code may have some of the subsystem's objects already created. In

* this case, it might be worthwhile to initialize the Facade with these objects

* instead of letting the Facade create new instances.

*/

int main() {

Subsystem1 *subsystem1 = new Subsystem1;

Subsystem2 *subsystem2 = new Subsystem2;

Facade *facade = new Facade(subsystem1, subsystem2);

ClientCode(facade);

delete facade;

return 0;

}执行结果

Facade initializes subsystems:

Subsystem1: Ready!

Subsystem2: Get ready!

Facade orders subsystems to perform the action:

Subsystem1: Go!

Subsystem2: Fire!

本文来自互联网用户投稿,该文观点仅代表作者本人,不代表本站立场。本站仅提供信息存储空间服务,不拥有所有权,不承担相关法律责任。 如若内容造成侵权/违法违规/事实不符,请联系我的编程经验分享网邮箱:chenni525@qq.com进行投诉反馈,一经查实,立即删除!

- Python教程

- 深入理解 MySQL 中的 HAVING 关键字和聚合函数

- Qt之QChar编码(1)

- MyBatis入门基础篇

- 用Python脚本实现FFmpeg批量转换

- DevEco Studio for Mac:zsh: command not found: ohpm

- 多路转接之epoll

- gh0st远程控制——客户端界面编写(二)

- 前端Vue进阶

- NodeJS 个性化音乐推荐系统-计算机毕业设计源码00485

- 山姆·奥特曼重新掌舵OpenAI,为人工智能“保驾护航”

- selenium iframe框架处理

- 基于数据挖掘的会务管理系统-计算机毕业设计源码84883

- 实名认证(身份证二要素)API在共享经济中的作用和优势

- 用云渲染好还是本地渲染好?